E.E. arrived just after dawn on September 16, 2021. and six other African immigrant men were resting in their bunks at the Glades County Detention Center in Moore Haven, Florida, when Captain John Gadson and a group of at least 15 sheriff’s deputies stormed in, as TruthoutThey pepper-sprayed them in their eyes before dragging them to solitary confinement.

E.E. The others sat alone with pepper spray burning their skins, and were forbidden from showering until the next morning. E.E. received paperwork on September 17. received paperwork with charges — but someone else’s name was on it. Nine days later, Glades and the others had a hearing. They learned that Glades would keep them isolated for 30 days as per Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), policy under the Department of Homeland Security.

“We are being targeted,” wrote E.E. in a formal complain to the DHS Office of Civil Rights and Civil Liberties.

Since 2017, seventy-seven of these complaints have been filed by or on behalf people detained at Glades, mainly for denials of medical care and excessive use of force. according toThe American Civil Liberties Union of Florida (ACLU) has created the Florida Detention Database. Advocates sayTestimonies such as these played an important part in the pressure which led to ICE’s decision on March 25 to “limit”The Glades County Detention Center. Understanding the history of the Glades County Detention Center shows why ICE’s attempts at reform are not enough.

“It May Smell Like Money to Some People”

Conditions in DHS’s immigration prisons have been under scrutiny the entire 20 years of ICE’s existence, just as the agency’s predecessors had also experienced critiques, arguably all the way back to Ellis IslandIn the 1890s. But there are major differences under ICE — namely, the massive scale of detention, both in the number of people and the amount of time they are held.

This has led to a significant increase in national and international attention and outrage about the immigration policies that have become a defining characteristic in the United States, along with its unmatched prison system. Groups that may have previously focused on reforms and piecemeal improvements via legislation and litigation are joining in the call for a complete “shut down” of ICE detention centers.

Nonpartisan groups such as the ACLU have joined smaller, often grassroots, volunteer-led organisations to issue powerful statements like this one from September 2021, by ACLU Campaign Strategist Isra Chaker: “While the Biden administration has halted some of the former administration’s cruelest policies, far too many unjust anti-immigrant policies remain, and thousands of immigrants are paying the price.” Chaker noted that, until the 1980s, most immigrants were not detained while navigating the legal process, but today detention has become the norm rather than the exception.

It is painfully obvious to anyone who takes a look at it, even the people who are not in the know. Government Accounting Office (GAO), which issued a report on ICE detention in February 2021. The report states that out of the $3.14 billion allocated to run its immigrant prisons it has spent hundreds of millions on empty beds. These beds are often paid for by private contracts.

These profiteering interests control over 70% of ICE facilities and lobby hard for their preservation.

In March 2021, Rep. Ilhan Omr (D-Minnesota), cited a similar profit motive and led a revolt. letter to President Biden’s Director of Domestic Policy Susan Rice and Secretary of Homeland Security Alejandro Mayorkas, calling for an end to ICE contracts with local jails and prisons. “Some of the worst examples of abuse and retaliation against detained immigrants during the COVID-19 pandemic … occurred in jails and prisons operated by localities,” wrote Omar.

In 2018, the Vera Institute’s “In Our Backyards” seriesThe, which looked closely at the financing of prisons and prisons in the U.S., did a deep dive into the history of one such local facilityGlades County, Florida: Contracting with ICE The history and the current happenings at Glades show a much larger picture of abuses and corruption at all levels. But also the resistance that is bringing about urgent changes to the country’s immigrant-detention policies.

Glades was highlighted in the Vera report by Vera. It revealed the dirty dealings that led to the financing of a much larger jail than the county could ever need. The Vera report also examined the county’s social history. Jacob Kang Browne and Jack Norton summarized it this way:

Glades County, now known as the county, was a refuge for people who wanted to live normal lives free from state-sponsored racial violence. Before Florida became a slave state in 1845 and was admitted to the union, Creek and other native people moved to Florida under Spanish control. They also accompanied enslaved African-born people fleeing the United States. Their descendants created the Seminole nation in what is now known as the Everglades — swampland that extends from present-day Orlando to the end of the peninsula. Many of their descendants were killed during the Seminole Wars, which occurred in the nineteenth century. They were also forcibly moved to Oklahoma by the U.S. government. Many of those who remained were moved to a number of small reservations, including the Brighton Reservation which lies within the borders of Glades County…

Kang-Brown and Norton note that in the 1920s and ‘30s, Glades County’s swampland was drained so sugarcane could be farmed there. Clewiston-based U.S. Sugar, in nearby Hendry County, now owns much of Glades County’s land. “During the harvest season, sheets of thick white smoke rise above the fields where workers burn the cane before harvesting and shipping it to the nearby refinery,” wrote Kang-Brown and Norton. Visitors to the Glades County Detention Center have reported seeing sugarcane ash in their cars and a distinct smell.

“It has an odor,” said County Commissioner John Ahern, in an interview with Kang-Brown and Norton. “It may smell like money to some people.”

Most of the land in the county — 86 percent — is farmland. Much of what isn’t U.S. Sugar’s property is owned and ranched by the Lykes Brothers corporation, where 65,000 cattleAs of 2020, the ratio is close to five to one.

It might be easy to see the area as another rural stronghold of reactionary and conservative politics, ideal for a prison economic. One closer look reveals a different picture. The Seminole- and Miccosukees living off South Florida’s reservation lands continue to feel unconquered. Historians consider the war against their community of Indigenous and escaped African refugees, which was waged in conjunction with the Trail of Tears, to be a significant part of their population being shipped out to Oklahoma. Richard J. Procyk as the “most protracted armed conflict engaged in by U.S. armed forces” until the Vietnam War. But resistance in the region is not a historical event from 150 years ago.

The Seminole have fought back against the U.S. government throughout the past century on issues such as relations to Cuba, gaming rights, land use and water usage; and energy infrastructure. Into the ’80s and ’90s, the more recently arrived local people, largely descendants of European settlers, have been fighting land use battles against the county’s cattle barons. After a campaign of sabotage against Lykes’ fences that limited public access to the county’s much-loved Fisheating CreekA 1998 victory in circuit court ruled the waterway belonged the people of Florida. This result liberated over 18,000 acres around the waterway from the commons.

Collier County, one county above Glades, is home to the farmworker stronghold of Immokalee, where the immigrant agricultural workers, primarily from Mexico, Central America and Haiti, have been capturing international attention since the ’90s and 2000s for labor sit-downs, blockades, hunger strikes and massive anti-corporate boycotts that brought multinational fast-food giants like McDonald’s and Taco Bell to the negotiating table.

This history provides the background for the fight against ICE at GCDC as well as the history of big sugar, corporate cowboys, and corruption.

“If You Build It, We’ll Fill It”

Since the construction of the immigrant detention center, Glades County commission meetings have had three predictable elements: the Pledge of Allegiance, a prayer for the county and Commissioner Ahern reporting on how many “customers” ICE is sending to the jail.

The county began building this $33 million facility in 2002, the same year that Congress — riding a wave of nationalism and xenophobia in the wake of 9/11 — passed the bipartisan legislation that created ICE. Glades County leaders built a 546-bed jail with about 450 beds for those in ICE custody, in the hope that this new agency would be able to imprison hundreds of immigrant families in their rural county.

“They said if you build it, we’ll fill it,” noted Stuart Whiddon, Glades’ sheriff at the time. The county would be able to make a profit if the jail was full. ICE would pay $80.64 per person, per dayAccording to records of ICE and county, the 2017 price was $90. Only 22 percent of that would go to food and medical careDetention has resulted in inevitably poor conditions for those held. Food was reported as frequently bug-infested and rancid; “shit water,” as one detained man called it, poured into sleeping areas from a broken second floor toilet; medical staff denied life-saving medications and surgeries. “The nurse told me that just having a heart attack or being on The floor is the only way to get me to the hospital,” another detained man reported.

Shaving what they spend on detained people down to a sliver has left sizable chunks for sheriff’s department wages, as their staff oversees day-to-day operations, and for investors.

Although the Glades jail is not owned by a private company like GEO Group, which does operate a state prison across the street, investors still hope to make a profit from the detention of immigrants. OppenheimerFunds, Inc., New York City, purchased a majority of the tax-exempt bonds. These bonds covered the entire $33million cost of building the jail and were expected to be repaid with interest. Lest the county be held liable if the bonds couldn’t be repaid, Glades County leaders, including Ahern and Whiddon, formed a nonprofit called the Glades Correctional Development Corporation as a buffer. The nonprofit was discovered by the IRS in 2017. converted the bonds to taxableto comply with new regulations. It had helped bondholders save $23.5 million in income taxes. Invesco acquired OppenheimerFunds in May 2019 and it now manages $229 billion in assets.

Over the years, Ahern’s reports on jail numbers have been riddled with anxiety. The jail almost closed in 2014, as detention numbers dropped to 68. Only during Donald Trump’s presidency was ICE consistently filling Glades with “customers.”

At every commission meeting, between the pledge of allegiance and Ahern’s “customer” report, the commissioners pray that they would do their best to serve Glades County. They don’t mention pepper spray, burning skin or eyes. They don’t mention the name of Valery JosephA 23-year-old Haitian man with learning disabilities, died at Glades in the year following the opening of the detention center. They never mention Onoval Perez MontufarA 51-year-old Mexican male died from COVID-19 in Mexico in 2020. And they don’t speak of the multiple women who have come forwardConcerning sexual harassment and violations to the Prison Rape Elimination Act.

Serving Glades County, according to the commissioners, means praying that their jail remains full.

“Boy, You’re in Glades County”

“When it comes to us, the Africans, they have a problem with us,” said one of the African men who was assaulted and pepper sprayed along with E.E. GCDC had been ordered to provide GCDC just one month prior to the targeted attack on these seven Africans, apparently for their race or ethnicity. pay damagesThey also detained five other African immigrants.

Before coming to Glades, these five had spent 40 hours shackled to their seats –– chained at the wrists, legs and waists –– on an ICE-chartered flight in December 2017, along with 87 other Somali men and women. The plane took off for Somalia. sat in Senegal for 23 hoursAfter stopping to refuel there, the deportation was abandoned and he returned to Miami. citing logistical problems.

The 92 Somalis claimed that they were forced to urinate inside bottles or in their chairs during the 40-hour flight. They were beaten and threatened, pulled down the plane aisles, denied medical treatment, and placed in full body restraints to ask guards questions. Some of the men sustained serious injuries upon landing in Miami. doctors reported.

After the horrors of their flight more than half the Somalis onboard were imprisoned at Glades. There, abuse continued. Glades staff “said things like, ‘We’re sending you boys back to the jungle,’” according to Lisa LehnerAmerican for Immigrant Justice attorney,. Similar to E.E., they were placed in solitary confinement without any reason. pepper sprayedThey were sprayed with the chemicals on their skin until they vomited. After that, they were denied the opportunity to take a shower to remove the burning chemicals.

Glades denied them the right of seeking solace in their faith rhythms through all this abuse. Glades was required to pay damages in a lawsuit filed February 27, 2019. stated that Glades prevented prayer services “deprived plaintiffs of religiously compliant meals and instead provided them with food that is inedible, nutritionally deficient, or both; and failed to provide Plaintiffs with essential and commonplace religious articles that are necessary for their religious practice, including Qur’ans, prayer rugs, and head-coverings.”

The chaplain was confronted by one of the Somalian nationals about this. allegedly retorted, “Boy, you’re in Glades County.”

History repeats itself in Glades County because no amount of oversight, bad press or even financial consequences seem to curb the sheriff department’s racist abuse.

Even in 2018, there was a complaint that documented the abuse of Somali nationals noted, “These allegations against Glades are not new. For many years, nonprofit organizations have documented abuses and inadequacies at Glades.”

Lehner added, “The guards and the administration up there at Glades, they think they’re immune. To me, it’s so brazen to be doing this. They know there’s a federal case. They know we’re up there all the time. They know there are investigators up there.”

The Glades County Detention Center is like ICE and has shown that it can’t be reformed.

“All Stuck in an Unsanitary Box Together”

The alleged pattern of brazen abuse at Glades, coupled with the profit motive that drives the center to skimp on life-saving medical care and basic sanitation, has made it one of the nation’s worst detention centers for COVID-19 infections. Onoval Perez Montefar, who arrived at Glades just one week before his death, was the victim of medical neglect. His niece has describedPerez Montufar tried to get medical care but was denied. He was not even taken into the hospital until one among his dorm room mates demanded an ambulance.

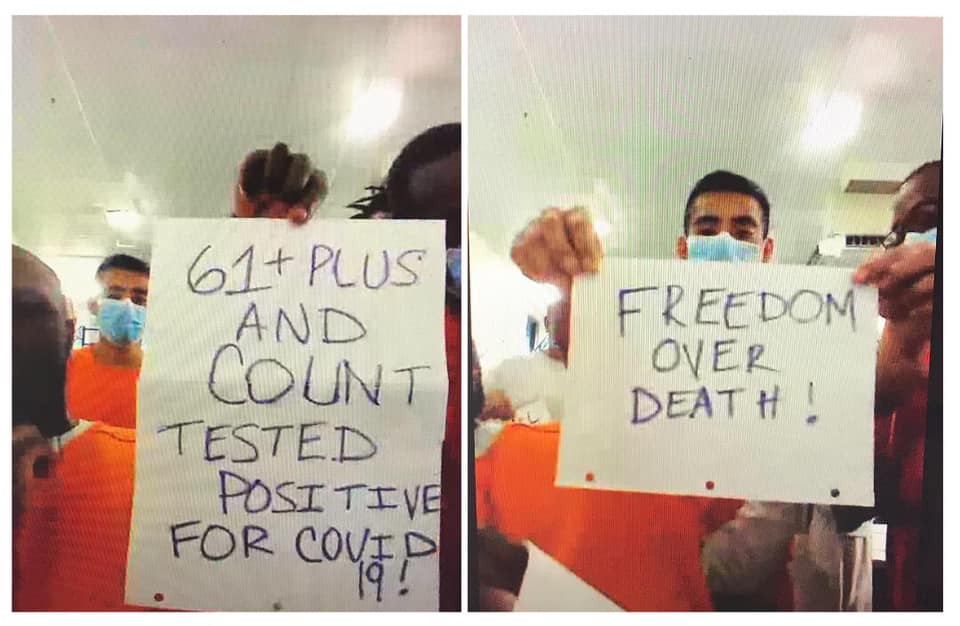

Glades detainees had feared this outcome for years. In March 2020, at the very start of the pandemic’s spread in the United States, about 100 detained immigrants at Glades went on hunger strikeThey used one of the few options of resistance to protest the degrading of already unhealthy conditions. The hunger strikers reported “a lack of antibacterial soap, lack of testing, overcrowding, inedible food and the danger posed by in-transfers from other facilities.”

It would be the first in a series of hunger strikes and other actions by Glades residents. COVID-19 spread quickly, leaving behind debilitating symptoms and death to hundreds of people. From the beginning of the pandemic, to the present, the conditions in which they are held have been protested by the immigrants who were imprisoned at this facility. In addition to hunger strikes, they also initiated federal complaints, commissary boycotts and op-ed articles, as well as a lawsuit against ICE.

They were part of a national resistance within the walls of detention centres. Detained people knew what COVID-19 would mean for them when it spread around the globe. It was impossible to socially distance themselves from the disease. They knew there would be no meaningful steps taken to clean up the filthy, deteriorating facilities. They knew ICE didn’t care about their lives.

“Please, if this gets out, we are helpless,” one detained person at Glades saidof the virus. “We are all stuck in an unsanitary box together.”

National hunger strike by immigrants. From late 2020 to early 2021, one hundred forty immigrants from Hudson and Essex, two county-owned facilities, went on strike for fifteen days. Just prior to that, immigrants in the Bergen jail went into hunger strike for a month. “We are tired of the inhumane treatment we receive from the authorities,” a hunger striker wrote. “We are tired of being treated like the worst criminals.”

35 immigrants were detained at York County Prison on August 20, 2021. went on hunger strikeTo demand their release from ICE after the county ended its contract. They wanted to be reunited with their loved ones rather than being transferred to a faraway facility after the facility was closed. ICE quickly retaliated to the York hunger strikers by denying them access phone, TV, and showers. Five of the strike’s organizers were thrown in solitary.

When York and Essex closed, many who had been detained there were sent a thousand miles south to Glades — including E.E. — in what appears to have been a retaliation transfer, using the poor conditions and known racism in Florida jails and prisons as punishment for resistance.

Many of the Northeasters who were transferred to Glades continued to resist and joined those already held at Glades. They’ve continued to file federal complaints, speak to the media and make public declarations.

Mid-September 2021 was the time when ICE filled Glades in with people and women from other countries. around 100 people went on hunger striketo demand immediate release, access to phones, sanitary conditions, personal protection equipment, and no deportations. The strikers also raised concern about how crowded the facility was as yet another COVID-19 outbreak tore through the facility and Glades kept everyone “quarantined” together: seriously ill people, people with symptoms and those who were still healthy — just as Glades has done throughout the entire pandemic.

“Winning the Fight of Our Lives”

Despite the fact the Biden administration taking steps towards improving the path for citizenship for some immigrants, nearly 5,000 more people are in detention in March 2022 that at the end Trump’s administration. The number of people detained had increased by nearly 5,000 since March 2022, when the Trump administration ended. dropped to 15,000 in January 2021, down from 38,000 in March 2020, pre-pandemic (which was also down significantly from May 2019, when ICE reported 52,398 detained immigrants — the highest in the agency’s history). Despite protests calling for its abolition, the number being held has continued to rise since the White House’s last change of hands.

“We did have hope for the Biden administration that they would at least very significantly limit or lessen the use of immigration detention,” said Kathrine Russell, an immigration attorney with RAICES(Refugee and Immigration Center for Education and Legal Service). “Unfortunately, that does not seem to have happened whatsoever.”

Advocates insist that citizenship is not enough as long as immigrant groups are being destroyed by trauma and abuse in Glades detention centers and deported to their families and communities.

“We cannot act like the path to legalization is a path flowing with milk and honey,” writes Subhash KateelFamilies For Freedom’s co-founder and former director was. “It is a necessary step in a path towards a greater vision of social justice.”

Kateel writes that a greater vision of social justice must be cultivated in immigrant communities.

We must stop talking about ‘good’ and ‘bad’ immigrants and build with those most affected. This is the only way we can build a movement with more substance. Families who have survived the prison-industrial system are not just charity cases or sad stories. They are people who have survived one the most complex systems society has for marginalizing someone.

Kateel says that the solutions must come directly from immigrants. They must also protect the lessons and experiences they have gained on their journey to freedom. Lastly, winning “the fight of our lives” must also confront DHS directly and creatively.

Kateel initially wrote these words in his essay, “Winning the Fight for Our Lives,” published by Prison Legal NewsThese outlets were listed in 2008 and included in a 2012 book collection. Beyond Walls and Cages.

It has been over a decade ago since its original publication. However, the core of this position rings true, louder and more frequently than ever after the past two year of COVID-19 related protests, uprisings or lawsuits from inside prisons.

“If the immigrant rights movement doesn’t understand raids, detention, and deportation in the context of the greater prison-industrial complex, and organize accordingly, we will lose the fight of our lives — a fight we can and must win,” writes Kateel, making the case that detained immigrants and non-immigrant prisoners, their families and support networks, have much to learn from each other.

“If Glades Continues to Break the Law, ICE Must Terminate Its Contract”

The fight for Glades isn’t over, but the Shut Down Glades Coalition — a grassroots group of local and national organizations — has seen wins, and a growing glimmer of future victories to come. Most significantly, by the latter part of March 2022, no one was detained in ICE custody at Glades, and on March 25, ICE announced that it was “limiting the use” of Glades, and would stop paying Glades for the guaranteed minimum of beds that it had begun funding during the pandemic (first 425 beds, and then 300).

“The long, disturbing record of inhumane treatment at this facility demands this move,” said Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz(D.Florida), who has led members in calling for a complete closing. “I will continue to closely monitor this contract, and press for its complete termination if anything close to the abhorrent mistreatment persists.”

The coalition is pushing for the contract’s end and its revocation. This is also happening in other jurisdictions across the nation, including two other county-run ICE centers in Florida, Monroe and Wakulla.

“Through our monitoring of immigration detention,” said Sofia CasiniDirector of Visitation Advocacy Strategies at Freedom For Immigrants. “We have documented that ICE often empty detention centres in the face of public scrutiny only for them to be refilled months later under a veil. We won’t let that happen here. Reform is not possible. This has been proven numerous times. The Biden administration must cut the Glades contract before it’s up for renewal next month.”

The Shut Down Glades Coalition points to media exposure of Glades’ abuses as central to their strategy. Members of Congress have called Alejandro Mayorkas, DHS Secretary, for their media coverage and social media pressure. twice nowThe detention center was closed down permanently. Recently, 17 members from the U.S. House were detained at the detention center. called for the immediate closure of GladesThe Biden administration alone had received at least 15 civil right complaints. DHS’ oversight divisions were prompted to launch investigations. Earthjustice, an environmental organization, joined the Shut Down Glades Coalition. on the Environmental Protection AgencyGCDC is being investigated for multiple exposures of immigrants to toxic chemicals multiple time per day. (Civil rights complaints requesting an investigation by DHS can be filed whenever a person’s rights are violated while they are in detention. You can file a complaint via the official DHS Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties form, or by writing a mail. Below is the mailing address and email address.

These complaints and actions are not the only ones that the ACLU of Florida and Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington have received. announced on January 24, 2022, that, unless Glades provides prompt redress, they will pursue legal action against the facility for illegally deleting video surveillance footage — a violation of federal regulations, which could be used to substantiate the multiple reports of abuse under investigation.

“The deletion of surveillance footage at Glades is the latest example of ICE’s appalling failure to follow and uphold critical recordkeeping laws,” said CREW Senior Counsel Nikhel SusIn a statement referring to filing their complaint with the ACLU. “It is shameful that ICE appears to be comfortable with keeping the public in the dark about abuses taking place in one of its detention centers. NARA and ICE [National Archives and Records Administration] must intervene as legally required, and if Glades continues to break the law, ICE must terminate its contract with the center.”

The CREW statement explains that Glades’ destruction of security footage isn’t the only example of ICE attempting to dodge recordkeeping laws. “In 2019, ICE obtained permission from the National Archives to destroy years’ worth of sexual assault and death investigation records from ICE facilities across the country — a plan later blocked by a federal judge following a lawsuit filed by CREW.”

Organizations with Shut Down Glades claim that the most important aspect of all this work is that deportations were halted and people were released.

Just days after E.E. E.E. was a participant in a federal complaint regarding the threats and brutality he was subject to at Glades. ICE attempted deportation of him and two other Liberian males who were also targeted. E.E. E.E. contacted his lawyer shortly after he was transferred to ensure a smooth deportation flight. Advocates in South Florida as well as those from the Northeast who had previously known these men, worked together in contacting members of Congress in Pennsylvania and Florida. These representatives demanded a halt in deportations. Social media was abuzz in calls for action. A small group of coalition members showed up unannounced at the ICE field office and demanded a meeting with the field office director — and then posted the video of ICE officials trying to dissuade them, until they eventually got their meeting. These three men were eventually granted Zholds, which temporarily halted their deportations while ICE and DHS Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties investigated the original complaint and the attempted deportation.

Soon after, a Liberian male, who was one of seven African immigrants was released.

E.E. was tried again by ICE. ICE tried to deport E.E. a second time. His deportation was stopped once more through advocacy and his own resistance.

Today, E.E. E.E. is now free. His immigration case is closed. He is now at home in Pennsylvania with his family. He said that the first thing he did after his release was spend time in Pennsylvania with his children. This is what many of the 22,000 ICE detainees also want to do. “If Glades is closed,” E.E. told the Shut Down Glades Coalition in January, shortly after his release, “the people who are there now should be released. People need to be with their families.”

DHS Civil Rights and Civil Liberties complaints can be emailed [email protected]You can also mail it to: U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties, Compliance Branch, Stop # 0190,2707 Martin Luther King, Jr. Ave. SE, Washington, DC 205281-0190.