I spent six-and-a-half years in prison. I spent a lot of that time working on a fiction manuscript. I had to search for the right way to do this. So do most writers in prison. Now there’s a book to help change that.

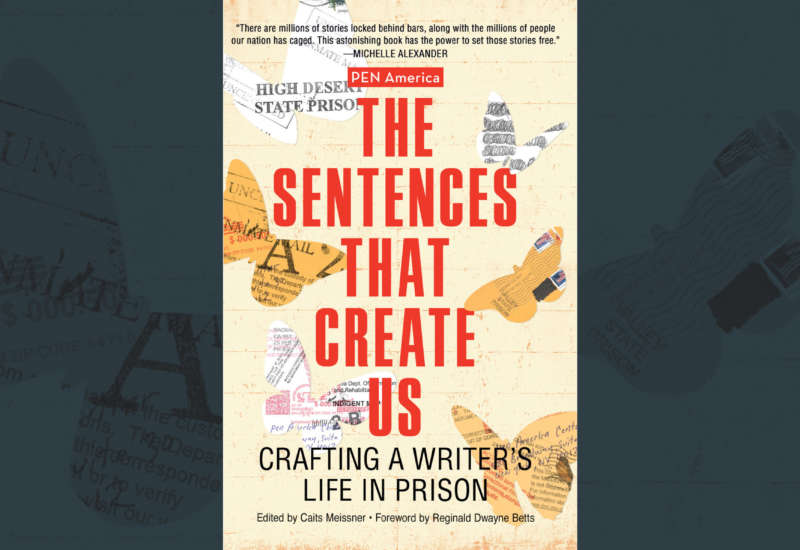

PEN America’s The Sentences That Create Us (Haymarket Books, 2022), edited by Caits Meissner, is the dream of every incarcerated writer: a collection of how-to-write essays by those who can speak to that audience best — other incarcerated writers plus people who have taught writing classes in prison. The book contains pieces by well-known writers, such as Wilbert Rideau, as well as those who have never published before. It offers advice on writing poetry and fiction, plays, and autobiography. The Sentences That Make Us HappyThis is a complete guide that is tailored to the needs of the target audience.

Meissner’s book will bring some welcome and profound relief to incarcerated people who struggle to tell their important stories. I had the pleasure to interview her. TruthoutAbout the book Frequent Truthout contributor Brian Dolinar — a friend, writer and fellow abolitionist activist in Urbana, Illinois — joined me for the conversation.

James Kilgore: Please tell us how you came up with the idea for the book and how it came about.

Caits Meissner: I taught prison for five to six year before I was allowed to take up my current position as director of Prison and Justice Writing. PEN AmericaFounded in 1922,, a non-profit organization that protects freedom of expression and brings together a national and international network. I was suddenly surrounded by famous writers and a remarkable community of incarcerated authors. This was my 40-year-old experience. programThat was the PEN initiative that I received in response to the 1971 Attica uprising. I had the chance to bring it into this new era where mass incarceration is actually something that’s talked about. Abolition is a word that’s being moved from the margins to the forefront.

PEN America had for many years created and distributed a handbook called The Handbook. The PEN America Handbook for Writers in Prison. It was essentially a book on writing, teaching the basics. When I came on, the director said, “I think you have a different pedagogy, I think you could do a new book.”

It needed the voices of justice-impacted people talking to each other. And speaking with allies, because we need each other — as we know, writers in prison need their allies on the outside. We need our prisoners to report from the frontlines and to be part of the community.

The task was then looking at all the mail that came in, the hundreds of letters we get from prison — what are people asking for? It became clear to me that people are really asking about not just “How do I write poetry?” … they were really asking, “How do I be a writer?”

I had access to all the amazing PEN incarcerated writers who had made incredible changes through the walls, and it was their own steam. I wanted them write revealing essays to help me understand and set in motion the journey.

Spoon Jackson and I had a conversation about Spoon’s piece. Spoon has done so many collaborations beyond the walls, he’s become a famous writer in prison. He said, “Well, I’m just real, it’s organic.” I said, “Yes, Spoon, but let me ask you this. When your writing instructor came in and it was a white woman, how did you respond to her in order to develop that relationship?”

I said, “Did you ask your collaborators to do things for you outside of your artistic collaboration?” He said, “Never! It a gift culture between two artists and I kept it there.” I said, “People need to understand that. There’s a lot of need in prisons. Your essay will be about analyzing each of these collaborations and how each was successful. That’s how we’re going to teach other people, how to show up in collaboration as an equitable artist, how to be seen that way, and how to see yourself that way.”

Kilgore: I’m wondering about the difficult task of how you decided who was going to be in the book. How did you manage this team? Did you hold meetings? How did you communicate? Did you visit people face-to-face?

It all came together in several ways. First, I knew that any money made from this book would be used to send the book inside. The book did not generate any profit, but I wanted to compensate contributors. The California Arts Council first granted us a $25,000 grant. This meant that all of the writers in the first section must be California-based and not incarcerated. The contributors to the rest of this book are mostly justice-involved.

I went through my so-to-speak “Rolodex” of relationships. Sometimes I had a clear idea of what I wanted people write about. Piper Kerman, author of Orange is the New Black), for example, I said, “I want you to write about how you write about people you know, ethically, given that your book turned into a major TV show.” And she agreed.

When I read the book, I thought of it as inspirational, aspirational and instructional, and then as historical. Wilbert RideauFormer editor of The Angolite. He is not one to give interviews but agreed to do an interview due to the book’s theme and the audience it was being used for. He ends the interview by sharing a truth he learned from his experiences and deeply believes: Writing is a way to get people out of prison.

Brian Dolinar: You’re sending copies of the book inside. How can you do that? How can you get around the censorship issues The authorities are always looking over people’s shoulders, reading their mail, listening in on phone calls. Did you worry about getting censored?

We were able to receive a grant from The Mellon Foundation to send 75,000 books inside. To find out where our allies were, we called every prison in the U.S. and asked where we could send the book. When the book came out, we also advertised with a form that we’re sending these copies inside and individuals and organizations can request the book. We’ve had over 50,000 requests within the first month of the book’s life, which tells me there is a hunger for this project.

There’s a couple of things I did worry about. This book, while it appears to be a lovely book on writing — if you look a little deeper, it’s a book on organizing in prison. It’s a book full life. And often prisons are very scared of the creative life force, because that’s personal power.

More than the book getting in was the book getting out, what would happen to the contributors? Thomas Bartlett Whitaker for example is included in this book. When I got my copy of the bound book, and I read it again, I remembered how profound his essay is; it’s called, “The Price of Remaining Human.” He writes about watching 161 men on death row be executed and their stories going with them. His own story is that he was sentenced to a shorter term than he was due to be executed. However, he has been subject to a lot of criticism from the prison administration for writing about death row and publishing online. He has a blog called “The Outsider” that he shares with his friends. Minutes Before Six.

As I was reading, I thought, “Wow, Thomas is already segregated!” [solitary confinement]He does this as a writer. It started to frighten me the world could double down on the punishment he gets for exactly what we’ve asked him to do. Of course, he took the project on knowing the risk, that’s what he’s writing about.

I’ll get calls from our Writing for Justice fellows who are fighting things in the prisons. Recently, one told me, “I’m about to go into solitary confinement for two months, you won’t hear from me, wish me luck.” The sense of responsibility of what it takes to become a writer in prison is immense.

Dolinar – Have you been inside since COVID was lifted and visitations resumed?

I visited San Quentin in December 2021, which was a very special experience for me. I did a book-tour in 2016 or 2017 to promote my poetry book. “Let it Die Hungry,”When I visited prisons. I had been to San Quentin’s Zoe Mullery’s writing group. After having not seen them in almost five years, I was able visit them again in December.

It was quite jarring to return to prison. It was also visceral to remember how oppressive it is. I was also reminded that there is a lot more to life behind the walls. One of the writers said a wonderful quote, “Imagination is a toy.” I shared about our new book. The men were thrilled. They kept saying, “We want to see this and this.” I was pleased to be able to say, “It’s in the book!”

I’ve visited over 25 prisons across the U.S., so I’ve talked to a lot of people. One of them is Sterling CunioA writer I met in PEN essay contest. He wrote this amazing essay about his purpose, hospice work in prison, and watching a man die. Sterling was sentenced to life without parole at 16, he was part of the “Oregon Five.” I later sat in on his parole hearing for six hours.

Sterling was made a Writing for Justice Fellow for 2019. Sterling was awarded money and a mentor to put on a prison play. I was able hear the performance via telephone. It was incredible. When the book came around, I said, “Sterling, can you write about how you staged this play?” Sterling had to lay out how he worked with administration, how he had to navigate the system and get permission to do good work. An antagonistic stance isn’t going to move projects forward.

Even though Sterling didn’t make parole at the hearing, his sentence was reduced a year later. Sterling is now in the 40s and is currently at home.

Kilgore – How do you view your book as a tool to support significant change in this terrible system of mass imprisonment that has dominated the landscape over the past four decades?

We need justice-impacted voices in order to change the system. We’re hoping to bring the voices of powerful, directly impacted people into major publications [and]Through narrative change, you can start to shift the needle.

There’s a sense that I come across from publishers that prison stories are a specialized niche topic. I respond that with 2.3 million people in prison at any one time, plus parole and probation, plus the families and friends of those affected, and communities affected, this is just another take on America’s story.