Humans have had an unprecedented impact on land – with vast consequences for climate change, food systems and biodiversity, a major new UN report concludes.

It says that human activities have already altered 70% of the Earth’s land surface, degrading up to 40% of it. Four of the nine “planetary boundaries” – limits on how humans can safely use Earth’s resources – have already been exceeded.

Food systems – a catch-all term to describe the way humans produce, process, transport and consume food – are the largest culprit when it comes to land degradation, the report says. They are responsible for 80% of deforestation and 29% of greenhouse gas emissions.

It adds that land degradation is perpetuated through inequalities. It notes that 70% of the world’s agricultural land is controlled by just 1% of farms, primarily large agribusinesses.

The report is from the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD), urges world leaders to adopt a “crisis footing” to solve land degradation. The authors warn that “at no other point in modern history has humanity faced such an array of familiar and unfamiliar risks and hazards”.

It projects that, if “business as usual” continues to 2050, an additional 16m square kilometres (km2) – an area almost the size of South America – could be degraded.

By contrast, if the world prioritises land protection and restoration, it could lead to the creation of 4m km2 of new “natural areas” by 2050, with benefits for tackling climate change and biodiversity loss.

This article explains. Carbon Brief walks through five key takeaways from the UN’s milestone land report.

What Is the UN Land Report?

The new report is by the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD). The Convention is the only legally binding framework that addresses desertification and the effects of drought and has 197 parties. It was established in 1994, via a direct decision at the 1992 Rio Earth SummitThe world was also given the name of the, UN Framework Convention on Climate ChangeThe Convention on Biological Diversity.

The UNCCD is focused on the rehabilitation, conservation and sustainable management of land and water resources and is the “custodian” for Sustainable Development Goal Target 15.3The aims of the, which is to:

“By 2030, combat desertification, restore degraded land and soil, including land affected by desertification, drought and floods, and strive to achieve a land degradation-neutral world.”

The second edition of the Global Land Outlook, (GLO2), has been five years in the making. It analyses future land scenarios, and the contributions of land based restoration to climate mitigation and biodiversity protection. UN Sustainable Development Goals. (The first editionThe drivers of the following were outlined in a 2017 publication. desertification.)

The report was created in partnership with 21 organisations and includes more than 1000 publications. Partners include the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the Convention on Biological Diversity(CBD) and the Indonesia-based Center for International Forestry Research(CIFOR), and Cape Town-based climate consultancy C4 EcoSolutions.

The report comes just two weeks before the UNCCD’s 15th “desertification COP” (COP15), scheduled to take place in Abidjan, Ivory Coast from 9 to 20 May this year.

The UN hopes COP15 will serve as “a key moment in the fight against desertification, land degradation and drought”, as parties step into what it describes as the UN Decade on Ecosystem RestorationFrom 2021 to 2030. This aims to prevent, halt and reverse ecosystem degradation “on every continent and in every ocean”.

Governments are expected to “build on the report’s findings” and offer a concrete response to the interconnected challenges of land degradation, climate change and biodiversity loss, the UN says.

The report is divided into 3 parts.

The first section focuses on the many problems land systems face: from biophysical factors in the Earth system to economic and social systems that rely on land.

The second part examines global land restoration practices and activities.

The third part evaluates the effectiveness of financial, national, and global restoration commitments. It sets out three scenarios through 2050: “business as usual”, a “restoration scenario” and a “restoration and protection scenario”.

UN Biodiversity chief praised the report Elizabeth Maruma Mrema(Who was interviewed in depth by Carbon Brief last month), who called it a “must-read for the biodiversity community”. In a statement, she stated:

“The future of biodiversity is precarious. Already, we have degraded almost 40% of the land and altered 70%. We cannot afford to have another ‘lost decade’ for nature and need to act now for a future of life in harmony with nature. The GLO2 shows pathways, enablers and knowledge that we should apply to effectively implement the post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework.”

Here, Carbon Brief presents five key takeaways from the GLO2 and their significance for the world’s climate and biodiversity.

1: Humans Have Already Transformed More Than 70 Percent of the Earth’s Land Area

Humans have already altered more than 70% of the Earth’s land area from its natural state, the report says.

This has caused “unparalleled environmental degradation” and contributed “significantly to global warming”, according to the report.

Because of human activity, an estimated $44tn – roughly half the world’s annual economic output – is being put at risk by the depletion of natural resources, the report says.

These resources “underpin human and environmental health by regulating climate, water, disease, pests, waste and air pollution, while providing numerous other benefits such as recreation and cultural benefits”, the report states.

It cites analysis finding at least 20% of the global land surface is now degraded – an area the size of the African continent. However, it adds that this estimate is “conservative” and notes that other assessments put the proportion of land degraded at between 20 and 40%. (The report says land degradation can happen “in many ways”, including through the loss of trees from forests, the conversion of grasslands to croplands and the over-exploitation of water and soil in drylands.)

Degradation is “particularly acute” in dryland regions, which are today home to one in three people, the report adds. Drylands are a collective term that refers to water-scarce regions of the globe, which include arid areas, semi-arid areas, and dry subhumid zones. The UNCCD’s definition of desertificationThese areas are prone to land degradation.

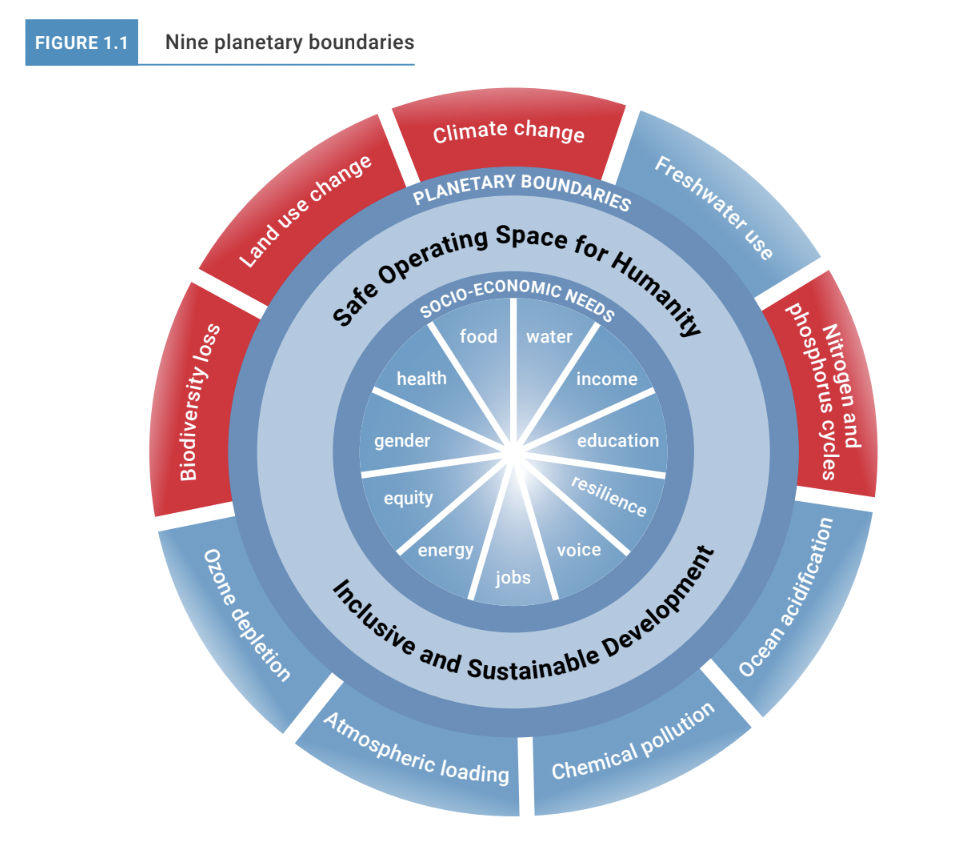

It says that of the nine “planetary boundaries” – limits on how humans can safely use Earth’s resources – four have already been exceeded: climate change, biodiversity loss, land use change and geochemical cycles (including, for example, the carbon cycle).

Below is a graphic that shows the four boundaries of the planets that have been crossed in red. (Many more are at high risk of being exceeded. Carbon Brief(Reported previously.)

The report says the breaches of the planetary boundaries are “directly linked to human-induced desertification, land degradation and drought”. It also adds:

“If current trends persist, the risk of widespread, abrupt, or irreversible environmental changes will grow.”

The report specifically addresses biodiversity loss and says that the numbers of mammals, birds amphibians, reptiles, amphibians and fish have declined by an average of 68%Between 1970 and 2016.

It adds that, in tropical central and South America, populations fell by 94% – “primarily due to land use change, largely the conversion of grasslands, savannahs, forests, and wetlands for agriculture and extractive industries”.

On land-use change, the report says that 5-10m hectares of forest were razed every year between 2000 and 2015, leading to a total global loss of 125m hectares – an area twice the size of France.

It adds that “hidden in the numbers is the loss of biodiverse and carbon-rich tropical forests”, which “have been offset by an almost fivefold increase in the rate of expansion of temperate forests”.

2: Food Systems Cause 80 Percent of Land Deforestation, 29 per cent of Greenhouse Gas Emissions, and Are the Single Most Significant Cause of Biodiversity Lost

“More than any other activity”, the report reads, modern agriculture is responsible for “alter[ing] the face of the planet”. At least 40% of the Earth’s land surface is dedicated to agriculture, and more than half of these lands are degraded.

Large-scale and industrial agricultural operations generate high levels of greenhouse gas emissions – 29% of the world’s total. Many of these emissions are due to deforestation or other land-use changes. According to the report, 80% of global deforestation is caused by agriculture, which also accounts for 70% of the world’s freshwater use.

According to the report, regulations have not been effective in protecting ecosystems from agricultural expansion. From 2013-9, more than two-thirds of agriculture-driven tropical forest clearance was carried out “in violation of national laws or regulations” – an area totalling 32m hectares, approximately the size of Norway.

Cattle, palm oil and soya are three of the largest culprits for this illegal deforestation, which is driven by “short-sighted national development priorities”, lax enforcement of existing regulations and “ultimately, consumer demand in developed countries”, the report states.

Deforestation is not the only cause of land degradation due to food systems. Agricultural expansion and climate change pose the “greatest threats” to grasslands, which make up more than two-thirds of the land being converted to cropland in wet regions of the planet.

Below-ground biodiversity and soil health have also “been largely neglected” by the transition to industrial agriculture, with serious ramifications. According to the report:

“While agricultural intensification can increase yields in the short term, unless done in a sustainable manner, it tends to cause high levels of land and soil degradation and contamination. Faced with long-term declines in productivity and water scarcity, farmers paradoxically resort to the increased use of harmful agrochemicals and inefficient irrigation systems.”

Industrialization of agriculture has led to the growth of large-scale agricultural businesses. Just 1% of the world’s farms control more than 70% of agricultural land, the report notes. However, 80% of farms are less than two hectares in size, which is only 12% of the total. At the same time, the report says, family farms are “key sources of the diverse diets that provide food and nutrition security for local communities”.

These small-scale farms are also more suitable for agroecological or other regenerative farming methods. The report lays out several case studies of communities where a shift towards “nature-positive” food production has resulted in the restoration or maintenance of ecosystems.

The example of this is the Campesino a Campesino movement – a grassroots ecological farming collective in Cuba – has helped farmers boost production without the use of agrochemicals, which are scarce and expensive in the country.

The report says that a “logical first step” towards reducing the impacts of agriculture would be a transition towards more plant-based diets. It notes that almost 80% of agricultural land is used to raise livestock, “while providing less than 20% of the world’s food calories”.

The report calls for the elimination of subsidies for farming practices that are harmful. More than $700bn of subsidies are paid out each year, the report says, but only 15% of this funding “positively impacts natural capital, biodiversity, long-term job stability and livelihoods”.

3: Protecting and Restoring Ecosystems Could Provide More Than a Third of the Land-Based Climate Action Needed to Meet Global Warming Goals

The report states that protecting and restoring natural environments could provide more climate action than one-third of the land-based climate actions needed to meet global warming targets between now and 2030.

A section of the report is dedicated to the role that land can play in “boosting climate action”.

It notes that the world has set a goal to limit global warming to well-below 2C by 2100 – with an aspiration of keeping temperatures at 1.5C – under the 2015 Paris Agreement.

Protecting and restoring land “reduces emissions and sequesters carbon”, the report says. It cites analysis finding that this could provide a third of the “cost-effective, land-based climate mitigation needed between now and 2030” to meet the Paris goals.

The report states that land-based climate solutions could help the world adapt to the effects of warming.

It says that “effective management and expansion of conserved and protected areas” and “ecological restoration or rewilding of biodiversity and well-functioning ecosystems” could play a role in climate adaptation.

The report also notes that, while the land and ocean have historically removed over half of the CO2 released by humans, the rate of removal “is now declining”. It continues:

“If land degradation continues unabated, this could potentially trigger a reversal from land being a net sink to being a net source.”

(As the first partYou can find the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) sixth assessment report explains (pdf): “…while natural land and ocean carbon sinks are projected to take up, in absolute terms, a progressively larger amount of CO2 under higher compared to lower CO2 emissions scenarios, they become less effective, that is, the proportion of emissions taken up by land and ocean decrease with increasing cumulative CO2 emissions. This is projected to result in a higher proportion of emitted CO2 remaining in the atmosphere.”)

The report states that land degradation is already contributing to climate changes.

Land-based CO2 emissions are largely caused by deforestation, burning, and draining of peatlandsIt also mentions soil degradation due to agriculture.

It cites the following: studyThis is what history has taught us., farming has released roughly 116bn tonnes of carbon into the atmosphere, with the rate of loss “increasing dramatically” in the last 200 years.

Emissions of methaneAnd nitrous oxideAccording to the report, two of the most potent greenhouse gases are nitrogen fertilisers and livestock rearing, respectively.

The report notes that climate change is not only caused by land degradation, but also by the effects of warming. It states:

“Hotter temperatures, along with longer, more intense droughts, wildfires, and extreme rainfall events, weaken ecological integrity and resilience in both managed and natural land systems.”

Because of human-caused climate change, “many forests and grasslands around the world are now more susceptible to pest and disease outbreaks” and crop yields have been “reduced”, the report says.

Climate change poses a particular threat to peatlands and permafrost, which “store huge amounts of greenhouse gases and provide essential services and unique habitats for many species”, according to the report.

It says that climate change is increasingly causing peatlands to “dry out” and causing permafrost to thaw.

Further degradation of these ecosystems could create “feedback loops” that could “surpass climate thresholds and accelerate global warming far beyond human control”. (For more information about climate tipping points see Carbon Brief’s dedicated explainer.)

4: Land Degradation Threatens Marginalized Communities the Most — But These Groups Have Much to Contribute to Ecosystem Restoration and Protection

According to the report, more than 3 billion people already suffer from desertification, land degradation, drought and other adverse effects. These are “mostly poor rural communities, small-scale farmers, women, youth, Indigenous peoples and other at-risk groups”.

These historically marginalised groups “are often the most exposed” to the risks associated with land degradation.

But land restoration measures that are not responsibly designed “could risk disenfranchising the most vulnerable and threaten their health, homes and livelihoods”, the report warns.

For example, expanding protected areas could have the unintended consequence of threatening Indigenous peoples who “legitimately occupy or claim these lands through customary systems that rarely are legally documented”.

Indigenous peoples represent around 6% of the global population, yet they act as stewards for at least 38m km2 – an area spread out across 87 countries and spanning all six inhabited continents. In total, Indigenous peoples have tenure rights over about one-quarter of the Earth’s surface, and 40% of intact ecosystems and protected areas.

However, Indigenous peoples have also been frequently forced from their lands and subjected to discrimination, with the result that “their fundamental rights and freedoms are often severely curtailed”, the report says. It also discusses the Land Back movement – a growing push for these communities to reclaim their ancestral lands. It states:

“The Land Back movement offers many opportunities for the restoration of traditional, regenerative land and water management practices, which could be applied throughout large parks, public lands, and protected areas. The movement is aligned with global campaigns to protect biodiversity, expand Indigenous management of protected areas and restore natural capital to mitigate and adapt to climate change.”

The US is an example of this. Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes in Montana in 1988 “led to increased species diversity and a healthier tree age distribution”. As a result, the forests on the reservation were “less prone to wildfires while providing better wildlife habitat and higher water quality compared to land managed by the US Forest Service”.

The report notes that “despite being a major store of carbon with great potential for achieving environmental and development goals”, rangelands – areas used for grazing or hunting animals – are “often neglected” in discussions of land restoration.

Around 500 million people around the world are pastoralists – typically nomadic livestock-keepers who occupy rangelands around the world. Their management of these ecosystems is “now threatened by climate change and mobility restrictions, as well as appropriation and encroachment”.

The report mentions examples of collective land tenure management from multiple continents as one possible method for maintaining pastoralist lifestyles.

Despite the fact that 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development calls for the protection and restoration of ecosystems, the agenda contains a “critical void”, the report says – “a lack of attention to the social and political dimensions of land restoration initiatives”.

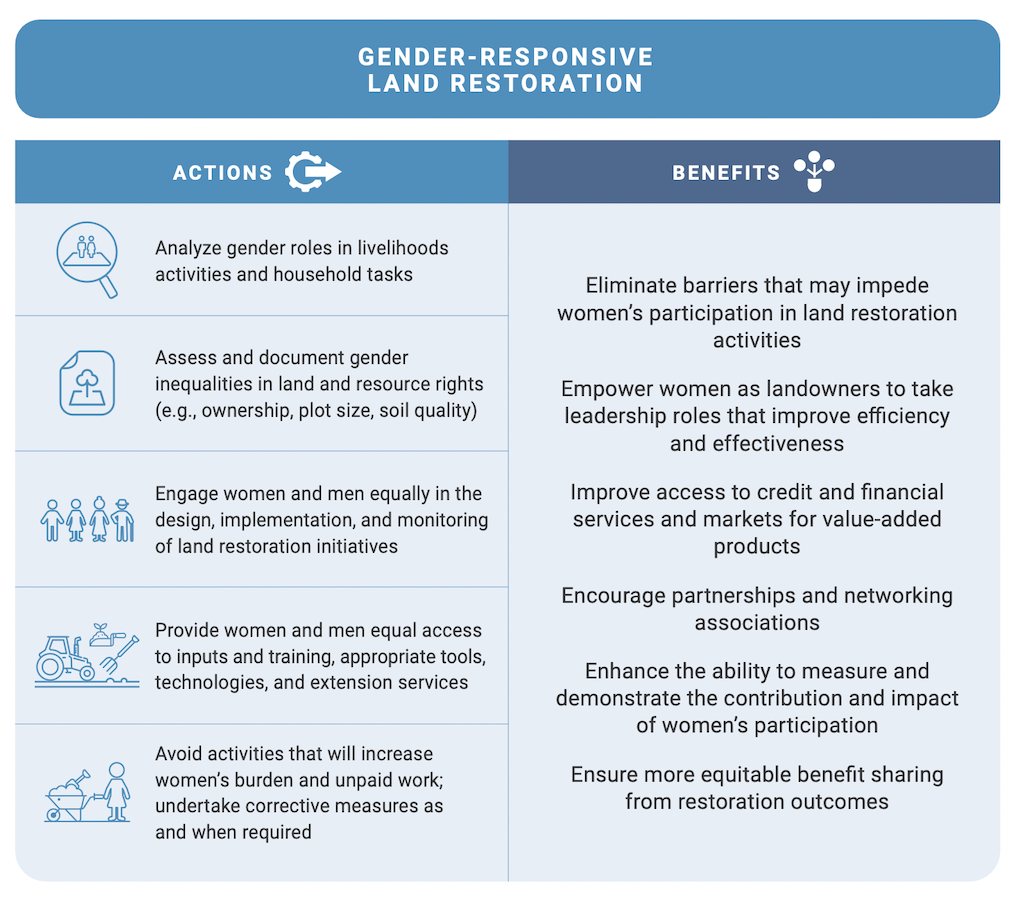

It notes that historically, programmes that have been “gender blind” have exacerbated existing gender inequalities, “with women’s access to land and natural resources further restricted, women’s voices and agendas undermined and their work burden increased”.

The report calls for “inclusive decision-making” processes to ensure equitable outcomes for marginalised communities. It states:

“Addressing past and ongoing injustices will help create a robust and enduring dynamic for future equity and sustainability through improved land management, social cohesion and more responsible governance.”

5: The World Faces a Stark Choice Between Protecting and Restoring Land and “Business as Usual”

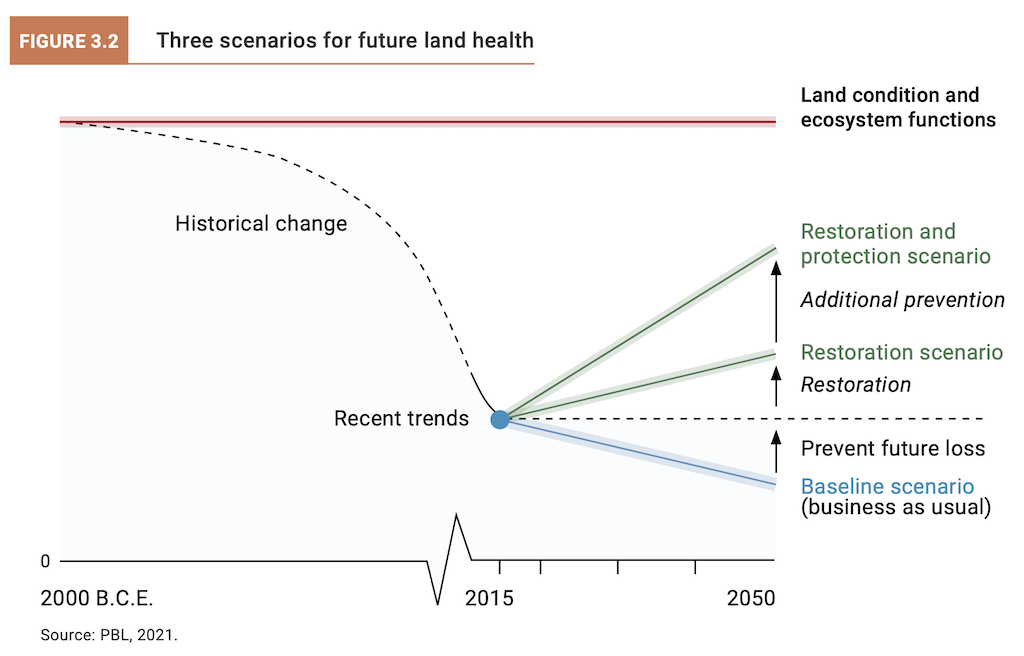

The report offers three scenarios for land between 2015-2050:

- A “business as usual” baseline scenario, where current trends in land and natural resource degradation are projected to continue through to 2050;

- a “restoration scenario”, where restoration is carried out on a “massive scale” and 5bn hectares of land (50m km2) are restored by 2050, through measures such as low- or no-till farming, agroforestry and silvopasture, improved grazing management, grassland rehabilitation, forest plantations and assisted natural regeneration;

- a “restoration and protection scenario”, where vital ecosystems are specifically restored and protected, in addition to other efforts.

These restoration scenarios for future land health are shown in the figure below, relative to current land commitments.

If the world proceeds at the pace of “business as usual”, the report estimates that by 2050, land almost the size of South America (16m km2) would show continued degradation.

In total, an additional 69bn tonnes of carbon would be emitted because of land-use change and soil degradation – divided between soil organic carbon (32bn), vegetation (27bn) and peatland degradation/conversion (10bn). Per year, these emissions “represent 17% of current annual greenhouse gas emissions”, the report says.

The report states that while agricultural yields will continue to rise in the future, land degradation will stop them from increasing and will increase the risk of drought and water scarcity. An agricultural slowdown could be especially acute in the Middle East, north and sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America, brought on primarily by the loss of organic soil carbon and soil’s ability to hold water and nutrients. Under this scenario, Sub-Saharan Africa will be the worst affected.

According to the report, nature and biodiversity are most affected by business-as-usual. Natural areas the size of India’s landmass would need to be cleared to feed a hungry world, with food demand projected to rise 45% between 2015 and 2050.

As a result, the report warns that “business as usual is not an option”.

Under the “restoration” scenario – where 16m km2 of cropland, 22m km2 of grazing land, and 14m km2 of natural areas are restored – 11% of biodiversity loss is averted, the report estimates.

Crop yields increase by 5-10% in most developing countries – especially in Latin America, north and sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East – and food price spikes are limited. Rain-fed crops would see soil water storage capacity increase by 4%.

Due to increased soil carbon and lower emissions, the stock of soil carbon would be 55bn tons higher in 2050 than it was in 2050. Russia, eastern Europe, Central Asia and Latin America will see the largest gains, while the “worst losses” will be averted in sub-Saharan Africa.

The “restoration and protection” scenario in the report envisages a world where land protection measures are expanded to cover close to half of the Earth’s land surface by 2050 – a threefold increase on the current coverage.

The report states that if this happens, an additional 83bn tons of carbon will be stored compared with the baseline.

“Avoided emissions and increased carbon storage would be equivalent to more than seven years of total current global emissions.”

However, this scenario would also mean escalating food prices – particularly in south and south-east Asia, where the report says a shortfall of agricultural land is “already impacting food security”.

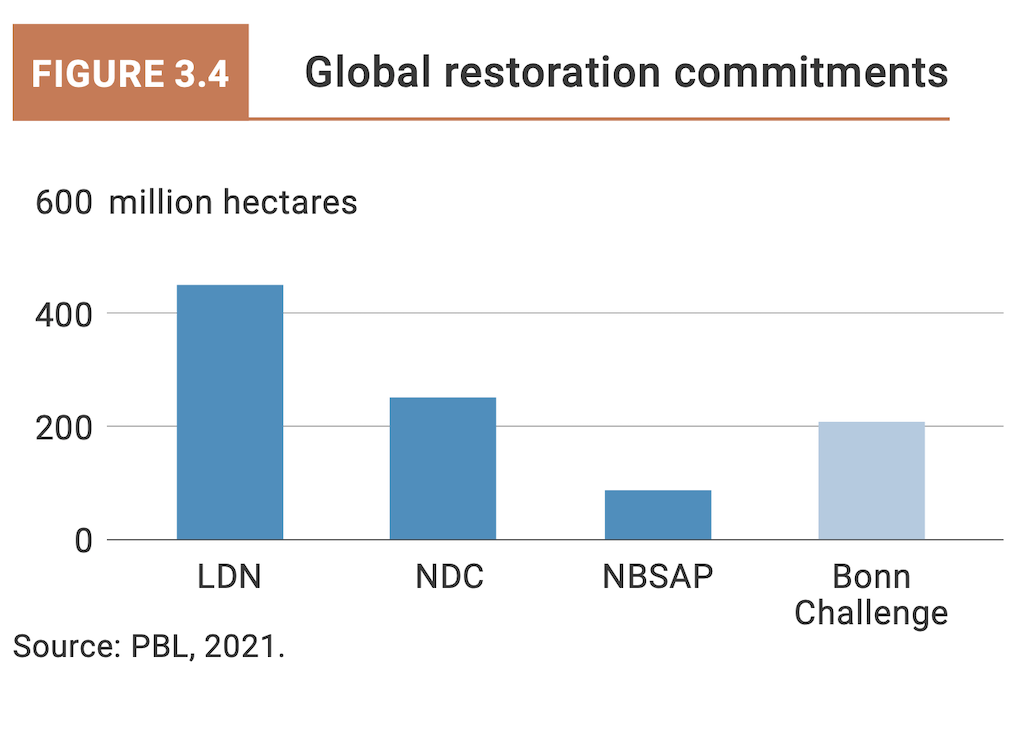

More than 115 countries have so far committed to restoring close to 10mkm2 of degraded land. This could be in their national biodiversity plans, climate plans, or voluntary pledges to the environment. Bonn ChallengeOr not. Today’s commitments, however, are “still insufficient to realise a nature-positive and climate-resilient future” and “must be backed by clear action plans and sustained financing”, the report says.

Below is a snapshot of how many land countries have voluntarily vowed to restore their land under the Nationally Determined Contributions(NDCs), under the Paris Agreement, Land Degradation Neutrality (“LDN”) pledges to UNCCD, National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans under the Convention on Biological Diversity and commitments towards the Bonn Challenge.

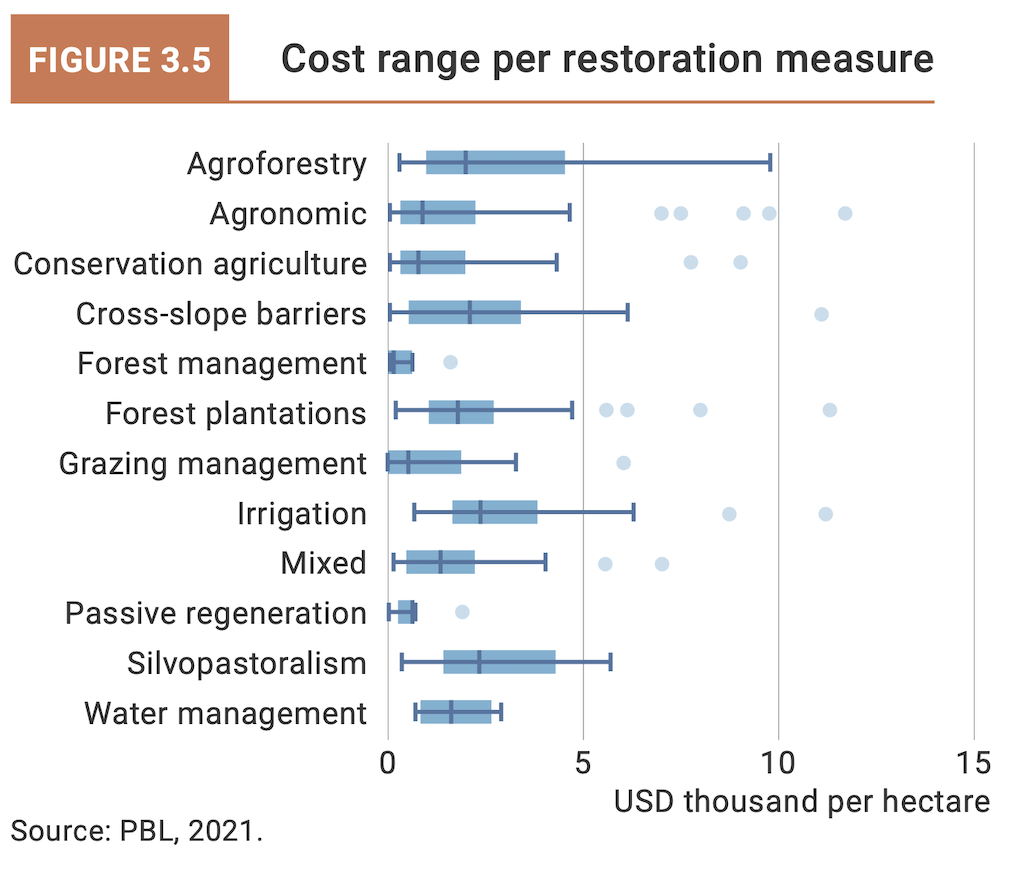

These commitments are estimated to cost between $305bn and $1.7tn – significant, but “far less than the amount of subsidies currently provided to the agriculture and fossil fuel industries”, says the report. Below is a breakdown of the estimated costs for most restoration measures.

The report says that to expect most developing countries to meet these costs would be “unrealistic and unfair” and they would need “extra-budgetary support in the form of investments, development aid (for trade), debt relief, or other financial instruments”. It also adds:

“Countries that are disproportionately responsible for the climate, biodiversity and environmental crises must do more to support developing countries as they restore their land resources and make these activities central to building healthier and more resilient societies.”

The report observes that “gender-responsive” land restoration – illustrated in the figure below – is an “obvious pathway” to reduce poverty and hunger.

It also finds that community-based restoration initiatives “tend to be the most successful” and that Indigenous peoples and local communities “represent a vast store of human and social capital that must be respected and embraced” to restore the planet.