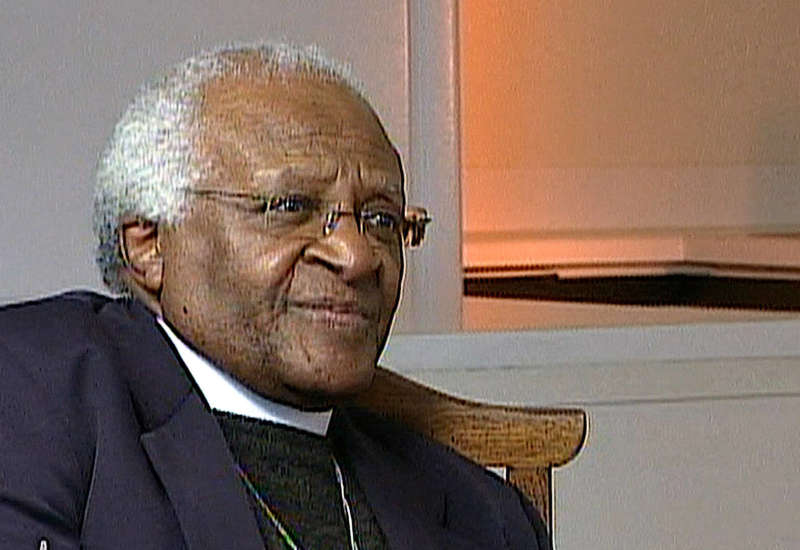

At 90, Archbishop Desmond Tutu of South Africa, an anti-apartheid icon has died. Desmond Tutu was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984 for his efforts to end white minority rule within South Africa. After the fall of apartheid in South Africa, Archbishop Tutu headed the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission. He advocated for restorative justice. He was a leader in the fight for human rights and peace throughout the world. He opposed the Iraq War. He also condemned the Israeli occupation on Palestine. He compared it with apartheid South Africa. We reair two interviews Archbishop Tutu gave on Democracy Now!As well as two speeches about the Iraq War, and the climate crisis.

TRANSCRIPT

This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN:Today, we dedicate an hour to Archbishop Desmond Tutu. The South African anti-apartheid icon, Desmond Tutu, died Sunday at the ripe old age of 90. Desmond Tutu received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984. He was recognized for his efforts in fighting against white minority rule. That same year, 1984, he traveled to Washington, where he denounced the Reagan administration’s support for South Africa’s apartheid government.

DESMOND TUTU:Apartheid is just as evil, immoral, and un-Christian as Nazism. And in my view, the Reagan administration’s support and collaboration with it is equally immoral, evil and totally un-Christian, without remainder.

AMY GOODMAN:In 1988, Archbishop Tutu was arrested after he organized a boycott of South African regional elections.

ARCHBISHOP DESMOND TUTU:I urge Black people of this diocese not vote in October’s elections. I also hope that white Anglicans will support their Black Anglican colleagues in this action. I am aware of the consequences for making this call. I am not resisting the government. I obey God.

AMY GOODMAN: After the fall of apartheid and the election of Nelson Mandela as South Africa’s first Black president, Archbishop Tutu chaired the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, where he pushed for restorative justice. Later, he would be a vocal critic. ANCThe African National Congress was founded under the leadership of Presidents Thabo Moki and Jacob Zuma. This is Bishop Tutu speaking in 2011.

ARCHBISHOP DESMOND TUTU: Hey, Mr. Zuma, you and your government don’t represent me. You represent your own interests. And I’m warning you. I warn you because of my love. As I warned the nationalists, I am also warning you. I am warning you: One of these days we will be praying for the fall of the enemy. ANC government.

AMY GOODMAN:Archbishop Desmond Tutu slammed the ANCIn 2011, the Dalai Lama was denied a visa because they did not grant one to him. He was invited to his 80th birthday party.

Archbishop Tutu was a leader in the fight for human rights around the globe. He opposed the Iraq War. He condemned Israel’s occupation of Palestine and compared it with apartheid South Africa. He backed the Palestinian-led elections in 2014. BDSBlowout, sanctions, and divestment movements. He also opposed torture and the death penalty. He recorded a 2011 video calling for Mumia Abu-Jamal, an activist and journalist from Africa, to be released.

ARCHBISHOP DESMOND TUTU: Mumia’s guilty verdict must be considered more than flawed. It is unacceptable. He has been denied the right for a new trial because of racial bias during jury selection. He has been subject to years worth of misconduct by police and prosecutions and judicial bias.

AMY GOODMAN:Today, we will spend the remainder of the hour listening to Archbishop Desmond Tutu speak in his own words. We will start by going back to February 15, 2003 when Tutu spoke in front of a large crowd in New York opposing the imminent U.S. invasion.

ARCHBISHOP DESMOND TUTU:People marched and demonstrated and the Berlin Wall fell. This was the end of communism. People marched and demonstrated and apartheid was ended. Democracy and freedom were born. People are now marching and demonstrating because they are saying no to war!

CROWD: No!

ARCHBISHOP DESMOND TUTU:We oppose war!

CROWD: No!

ARCHBISHOP DESMOND TUTU:According to the just war theory, you need a legitimate authority in order to declare war and wage war. This legitimate authority is only the United Nations. Any other war would be immoral. The just war says, “Have you exhausted all possible peaceful means?” And the world says, “No, we haven’t yet!” And any war before you have exhausted all possible peaceful means is immoral. And anyone who would wage war against Iraq should know that it would be a moral war.

The people who are going to die in Iraq are not collateral harm. They are flesh-and-blood human beings. They are children. They are mothers. They are brothers. They are both grandfathers. You know what? They are our brothers and sisters, because we all belong to the same family. We are members of one family, God’s family, the human family. How can we claim that we want bombs to be dropped on our siblings and brothers, or on our children?

We said no to communism. We opposed apartheid. We rejected injustice. We opposed oppression. And we said yes, to freedom and democracy. Now, I ask you: What do you think about war?

CROWD: No!

ARCHBISHOP DESMOND TUTU: I can’t hear you. What are you going to say about war?

CROWD: No!

ARCHBISHOP DESMOND TUTU:What are you going to do about death and destruction

CROWD: No!

ARCHBISHOP DESMOND TUTU:What are your thoughts on peace?

CROWD: Yes!

ARCHBISHOP DESMOND TUTU: I can’t hear you. What can you say for peace?

CROWD: Yes!

ARCHBISHOP DESMOND TUTU:What can you say about life?

CROWD: Yes!

ARCHBISHOP DESMOND TUTU:What would you say to freedom?

CROWD: Yes!

ARCHBISHOP DESMOND TUTU:What can you say to compassion?

CROWD: Yes!

ARCHBISHOP DESMOND TUTU:We want to tell President Bush to listen to the people. Many times the voice is God’s. Vox populi, vox dei. Listen to the people’s voice and give peace a chance. Give peace a chance. And let’s say once more so that they can hear in the Pentagon, they can hear in White House: What do we say to war?

CROWD: No!

ARCHBISHOP DESMOND TUTU:What are our words for peace?

CROWD: Yes!

ARCHBISHOP DESMOND TUTU: Yeah!

AMY GOODMAN:The speech of Archbishop Desmond Tutu at the massive antiwar rally held in New York City on February 15, 2003, when millions marched for peace. When we come back, we’ll hear the Nobel Peace Prize laureate talk about Guantánamo, torture and more. Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: “A Song for Bra Des Tutu” by Winston Mankunku Ngozi. This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman. We’re continuing to remember the life and legacy of former South African Archbishop Desmond Tutu, who died Sunday at the age of 90. I interviewed him several times over the years. I interviewed him in 2004. spoke to him at The Culture Project after a play about Guantánamo. I began by asking Archbishop Desmond Tutu what his response was to what was happening at Guantánamo.

ARCHBISHOP DESMOND TUTU:I thought that I knew what was going on, and I was shocked when I saw the play yesterday. I was particularly so because I had such an awful sense of déjà vu. For someone coming from South Africa, you say, “But, I mean, that’s exactly what they were doing for exactly the same reasons that they gave.” I mean, you said, “Why do you detain people without trial? Why do you ban people as you are doing?” And the response from the South African government was, “Security of the state.” And anyone who questioned it would then be regarded, especially if you’re white, as being unpatriotic.

And I just want you to know: Do you want it done in your honor? Isn’t it time there was the same sense of outrage that people had about apartheid, which people should have had about the Holocaust? What would happen if Americans were held captive by another country in these conditions? The fact is, God doesn’t have anyone. The god we worship is bizarre. Although they claim that this god is omnipotent and God is very weak, they also say that he is omnipotent. There’s not a great deal that God seems to be able to do without you.

AMY GOODMAN:You were a strong advocate for nonviolence in South Africa during the years before apartheid ended. Yet, you witnessed so many people being detained and even killed. What do you feel now, and how did you feel in those days? How did you get through those difficult days? What did you stand for? What did you do to keep your principles of nonviolence intact?

ARCHBISHOP DESMOND TUTU: One of the wonderful things actually is — well, I’ve got to speak as a Christian — is belonging to the church and knowing that you belong to this extraordinary body. When things were really rough, it’s wonderful to recall for me now that I sometimes got — when the South African government had taken away my passport, I got passports of love from Sunday school kids here in New York, and I plastered them on the walls of my office. But although I couldn’t travel, hey, here were all of these wonderful people all over the world. And I had a — I met a nun in New York at a particular time, and I asked her, “Can you just tell me a little bit about your life? How do you” — and she said, “Well, I am a solitary. I live in the woods of California. I pray for you. My day starts at 2:00 in the morning.” And I said, “Hey, man! I’ve been prayed for at 2:00 in the morning in the woods in California. What chance does the apartheid government stand?” So, one was being upheld.

And, you know, when frequently you say to people, the victory that we won against apartheid — a spectacular victory — that would not have happened without the support of the international community, without the support of people like yourselves, without the support of those who were students at the time, who might have been crazies, but they were fantastic in their commitment. They actually showed that you can change the moral climate in this country. The Reagan administration was at the time completely against sanctions. Students, but not just students, were willing to be arrested on our behalf. They also managed to override the veto of Congress, which was amazing.

So, it just happened. I always said that I was a leader by default, because the real leaders were either in prison or exile. And sometimes when people say, “And he got the Nobel Peace Prize,” I say, “Well, actually, you know, it was that they thought maybe it was time it was given to a Black,” and, ah, he has an easy surname: Tutu. Tutu. Imagine. Imagine if I had a surname like Wukaokaule.

AMY GOODMAN: Archbishop Tutu, how do you feel — how do you feel about —

ARCHBISHOP DESMOND TUTU:That is easy!

AMY GOODMAN:What do you think about the invasion and occupation in Iraq?

ARCHBISHOP DESMOND TUTU:It was incredible to see so many people come out in opposition. It was incredible. You know, sometimes when you say, “Ah, Americans,” or, “Oh, people nowadays don’t care,” it’s not true. Millions of people were wrong. Millions. Millions said, “No. Give peace a chance.”

And I said, as so many others — I mean, I wasn’t the only one. The pope also said so. The archbishop from Canterbury also said so. The Dalai Lama agreed. However, this war, if it were to be justified according to the justwar theory, would need to have been declared by a legitimate power. This was something that the administration knew. That’s why they went to the U.N. There’s no point in going to the U.N. if you had already decided — they probably, of course, had decided, but, I mean, there was no point unless they believed or they realized, I mean, that in order for it to be legitimate, and therefore justifiable, the only authority would have to be the U.N. And when they didn’t get what they wanted from the U.N., they did what they did. We said it then and we will keep repeating it, that it was illegal and immoral.

And the consequences of it just now — I mean, you have to be — you’ve really got to be blind to say, “Well, yeah, it’s OK. We removed Saddam Hussein.” Why didn’t you say that was the reason for going? Because the world would have said, “No, no, no, no. That isn’t a reason that will be allowable for you to declare war.”

And I’m sad. I’m sad that we seem so inured now. They tell you a hundred people have been killed, and the United States and its allies are doing that, and they say, “No, no. We targeted that house because our intelligence said so.” Intelligence. The same intelligence which said there were weapons to mass destruction? Please. That’s been done in your name, that mothers and children have been killed. And when you say, “What about the civilian casualties?” they say, “Sorry, our intention was to target insurgents.” And most of us, I think, just shrug our shoulders.

You did, however, experience a small amount of what is done on a regular basis on September 11th. And they are not — they’re not casualties. Collateral damage. Collateral damage, I tell you. How would you feel when someone calls the collateral damage to the victims of the World Trade Center attack and Washington, D.C. terrorist attacks collateral damage? Speak it to someone who has lost a spouse. Speak it to someone who has lost a spouse or a child. Collateral damage. It’s an obscenity. It’s an obscenity.

AMY GOODMAN:The South African Archbishop Desmond Tutu was 90 years old when he died on Sunday. I interviewed him at The Culture Project after a play about Guantánamo in 2004. Seventeen years later, Guantánamo remains open, and U.S. troops remain in Iraq. When we come back, we’ll hear Archbishop Desmond Tutu on Palestine, war, the climate crisis and more. Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: “Woza Moya” by South African jazz musician Herbie Tsoaeli. This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, as we continue to remember the life and legacy of South African Archbishop Desmond Tutu. He died Sunday. His funeral will be held on New Year’s Day. We now turn to an interviewI did the same with him in November 2008. We spoke at the South African vice consul’s apartment in New York.

AMY GOODMAN: Archbishop Desmond Tutu, it’s a pleasure to have you on Democracy Now!

ARCHBISHOP DESMOND TUTU:We are very grateful.

AMY GOODMAN:Your reaction to the election as the first African American president by a son of a Kenyan man?

ARCHBISHOP DESMOND TUTU: Yippee! No, “yippee” actually — it captures something that is almost ineffable. It’s very close to the kind of feelings we had on April the 27th, 1994. And some, maybe a few people in this country, have said it was, as it were, the Mandela — Mandela moment. It’s a moment when especially people of color have a new spring in their step — they can walk a great deal taller than they used to — and that even though this country, the United States, experiences very considerable racism — I mean, people being dragged to their deaths behind trucks — yet it’s a country that, in fact, has had this extraordinary experience. And it’s something that has filled people with hope that the world can be a better place.

AMY GOODMAN:How did it feel for your? Millions of people voted for Barack Obama in this election. How did it feel for your? How old were your first votes in South Africa?

ARCHBISHOP DESMOND TUTU: Sixty-three.

AMY GOODMAN:Is sixty-three years of age?

ARCHBISHOP DESMOND TUTU: Yes, yes.

AMY GOODMAN:What year was that? What year was it?

ARCHBISHOP DESMOND TUTU: 1994.

AMY GOODMAN:For the election.

ARCHBISHOP DESMOND TUTU:1994 was the first time that Nelson Mandela had ever seen it, and he too was an extraordinary human being.

Actually, in a way, you would say white people who had always voted in racially discriminated elections were voting for the first time, voting for the first time in a democratic — truly democratic — election. We were all on the same page, so to speak.

But it was — I said then, when I was asked, “What is your — how do you describe how you feel?” I said, “Well, how do you describe falling in love? How would you describe red to someone who is completely blind? How do you talk about the glories and beauty of a Beethoven Symphony to someone who is blind? Well, it’s like that. I mean, I’m over the moon. I’m on cloud nine,” as were most of my, if not all of my, compatriots on that day.

AMY GOODMAN: What do you think is Barack Obama’s greatest challenge as president of the most powerful country on Earth, following eight years of George W. Bush?

ARCHBISHOP DESMOND TUTU: Yes. Very clearly, it has been the fact that for those eight years you’ve had an America that followed a unilateralist line, an America that would not ratify the Kyoto Protocol on climate change. Most of the world had, and America just said, “Go jump in the lake.” Most of the world had ratified the Rome Statute that set up the International Criminal Court, which is where the people who were responsible for September the 11th should have been appearing.

That you are going to have — most people believe that he is going to be welcomed as the leader of the free world who will be more collaborative, who will be more consultative, who will not seem to want to throw the considerable weight of America around and seem to want to be the bully boy.

I have said — I did a piece for The Washington Post, and I said one of the things that would demonstrate a clean break from the previous administration would be closing the abomination Guantánamo Bay. And one would then hope that there would be a much more conciliatory approach to Iran, not, let’s say, the belligerence that has largely characterized the Bush administration. And I would hope, too — and that’s a major challenge — that there will be something to be done to bring a viable peace proposal for the Middle East, to end what I reckon is an unconscionable suffering of the Palestinian people. We must end the use of Qassam missiles against Israeli citizens.

AMY GOODMAN:You were prevented from going to Gaza in 2006 as you led a U.N. delegation after the killing of several Palestinians.

ARCHBISHOP DESMOND TUTU: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN:What should you do now about the Middle East? Specifically, Israel and the occupation.

ARCHBISHOP DESMOND TUTU: There’s been some very interesting moves with the outgoing prime minister suggesting that Israel has to consider very seriously the proposal of going back to the boundaries of 1967. That’s a very important initiative, if that was taken.

I think we would need to move quickly to lift the embargo. It is unacceptable to suffer. It’s totally unacceptable. It doesn’t promote the security of Israel or any other part of that very volatile region. It is contrary to the best teachings in the Jewish faith. I am aware that there are many Israelis who oppose what is happening.

And I pray fervently that there will be a boldness, you know, in saying we’ve got to resolve this, because I think if that — well, no, let’s not say “if,” because a lot hinges on what happens in the Middle East. Let’s say, when that is resolved, what we will find, I mean, that the tensions between, say, the West and the Muslim world, and large part of the Muslim world, I believe, myself, what we will find that that evaporates and that this — this is a saw, chafing, and it’s mucking up too many things. And I pray that this new president will have the capacity to see we’ve got to do something here, for the sake of our own humanity, you know, for the sake of our children.

AMY GOODMAN:Would you compare Gaza’s occupation to apartheid South Africa?

ARCHBISHOP DESMOND TUTU:I must speak about what I know. I mean, most people — a Jew will usually speak about their experiences and maybe compare whatever it is that is happening with what happened in the days of the Holocaust. For me, coming from South Africa and going — I mean, and looking at the checkpoints and the arrogance of those young soldiers, probably scared, maybe covering up their apprehension, there’s no way in which I couldn’t say — of course, that is a truth. It reminds me — it reminds me of the kind of experiences that we underwent. I mean, I was bishop of Johannesburg and would be driving from town to Soweto, where we lived, and I would be driving with my wife, and we’d have a roadblock, and the fact of our having to have passes allowing us to move freely in the land of our birth. And now you have that extraordinary structure that — the wall.

And I do not, myself, believe that it has improved security, breaking up families, breaking up — I mean, people who used to be able to walk from their homes to school, children, now have to take a detour that lasts several — I mean, it’s — when you humiliate a people to the extent that they are being — and, yes, one remembers the kind of experience we had when we were being humiliated — when you do that, you are not contributing to your own security. And all you are doing is you are saying to those people, in all of their desperation, “We are still human, and there are things we will not be able to accept — I mean, just sit down. We’ll have to — we have to do something.”

So you have the suicide bomber. And one does not condone them, but one understands perfectly how people can be driven into a corner, and out of that desperation — and so you have that cycle, the response of Israel to the suicide bomber, which you know is going to provoke another cycle. And one says, “No way, that’s not how God intended to us live,” that it is possible — it’s been shown: It happened in South Africa — it is possible for people who have been enemies to begin to think that they can be friends, at least to coexist.

AMY GOODMAN: The International Criminal Court — should Barack Obama as president sign on to the ICCSign the International Criminal Court treaty

ARCHBISHOP DESMOND TUTU: Yes. If you believe that the rule of law is a good thing, then you will be able to answer yes. This is a very important instrument because it is an instrument that says we will not tolerate impunity. Many are guilty, as you see right now in the DRC or in Darfur, that people who are guilty of egregious violations have to be brought to book, and it’s got to be done in a way that satisfies those standards that we have. I mean, you don’t hold people in detention without trial. That’s what the world used to say against the South African government. It was also true that it was wrong.

AMY GOODMAN:Obama, the President-elect, supports an end of the War in Iraq and a surge in troops in Afghanistan. What would you say to him?

ARCHBISHOP DESMOND TUTU: Well, I say that obviously it’s to end the war — yeah? — to end the occupation, to — but I’ve also said it would wonderful if, on behalf of the American people, he were to apologize to the Iraqis and to the rest of the world for an invasion that was based on lies.

AMY GOODMAN:The late Archbishop Desmond Tutu from South Africa. I interviewed him at the South African vice consul’s apartment in New York in November 2008, just after the election of Barack Obama. Sunday saw the passing of Desmond Tutu at the age 90. We end today’s show with the archbishop speaking to a group of youth climate activists outside the U.N. climate summit in Copenhagen in 2009.

ARCHBISHOP DESMOND TUTU:I want to thank everyone, especially the beautiful young ones, for their support. We oldies have made the world a mess. We want to encourage leaders to look in the faces of their grandchildren when they meet.

Climate change is a serious problem today. But we can make changes. If we don’t — if we don’t — hoohoo!, hoho! — there’s no world which we will leave to you, this generation. You won’t have a world. You will drown. You will burn in drought. There will not be food. There will be flooding.

There is only one world. We have one world. If we mess it up, there’s no other world. And for those who think that the rich are going to escape — hahaha! — we either swim or sink together. We all have one world. We want to leave a beautiful, beautiful world for the next generation of young people. We, the olderies, want to leave a beautiful world. It is a matter morality. It is a question about justice.

AMY GOODMAN:The late Archbishop Desmond Tutu, South Africa, speaks to youth climate activists outside of the U.N. climate summit. Copenhagen 2009. Sunday was his 90th birthday. His funeral will be held on Sunday — on New Year’s Day. You can view all our interviews and hear the speeches of Archbishop Tutu at www.tutu.org democracynow.org.

Brendan Allen, Mike Burke and Mike Burke deserve special thanks. Democracy Now! is produced with Renée Feltz, Mike Burke, Deena Guzder, Messiah Rhodes, Nermeen Shaikh, María Taracena, Tami Woronoff, Charina Nadura, Sam Alcoff, Tey-Marie Astudillo, John Hamilton, Robby Karran, Hany Massoud and Mary Conlon. Our general manager is Julie Crosby. Special thanks to Becca Staley and Paul Powell, Mike Di Filippo (Mikel Nogueira), Hugh Gran, Denis Moynihan and David Prude, as well as Dennis McCormick. I’m Amy Goodman. Stay safe. Wear a mask.