We speak with Dr. John Nkengasong, head of the Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to learn more about how vaccine inequity can lead to more coronavirus variants. Dr. John Nkengasong states that only 10% are fully immunized in Africa. Africa is home to 1.3 billion people and millions of vaccines. COVAXThey were quickly thrown away. Several countries in Africa have started to manufacture their own vaccines. “We have to shift our focus to vaccinating — that is, making sure that vaccines that are arriving at the airport actually get into the arm of the people,” says Dr. Nkengasong.

TRANSCRIPT

This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be final.

AMY GOODMAN: Global health experts warn that Omicron variant, a highly infectious disease, is increasing in undervaccinated regions of the globe. Only about 62% of the world’s population has received at least one shot, and the divide between the rich and poor regions remains vast. This is Mike Ryan, World Health Organization Emergencies Director, speaking virtually last week at the World Economic Forum.

DR. MICHAEL RYAN: Only 7% of the African regional offices states are represented in Africa. The reality is that the world is moving towards 70%; the problem is that we are leaving behind huge swathes.

AMY GOODMAN: According to the World Health Organization, the large vaccine gap could lead to another dangerous variant. Top African health officials claim that nearly 3 million doses of vaccine have been withdrawn from the continent. Many of the doses given by were not used. COVAX In particular countries, the shelf lives were short and they arrived quickly.

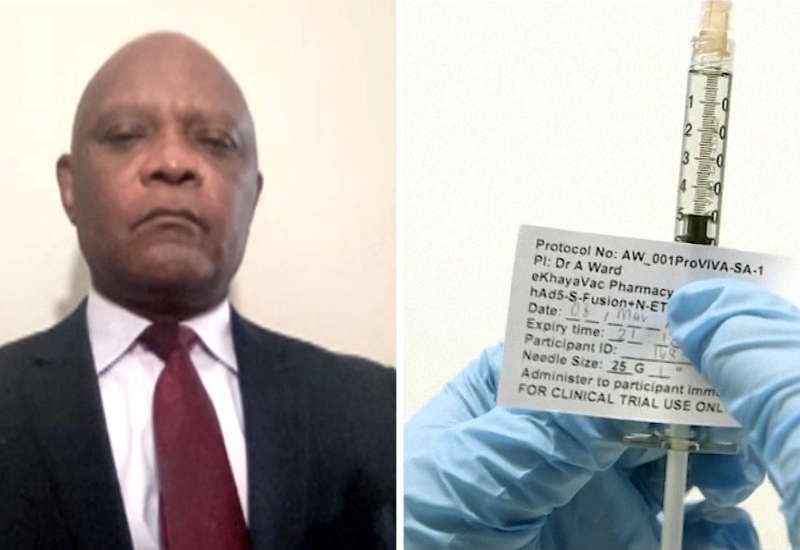

For more, we’re joined by Dr. John Nkengasong, director of the Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, an institution of the African Union. He just wrote an article. op-ed In The New York Times headlined “There Will Be Another Variant. Here’s What the World Can Do Now.” He last joined us from Addis Ababa. Today he’s in Washington, D.C.

Dr. Nkengasong, welcome back to Democracy Now! Talk about the current state in the world and Africa, especially when it comes to coronavirus. What can be done?

DR. JOHN NKENGASONG: Thank you so much for having me on the program again.

2022 must be the year we tip the balance in favor a greater number of vaccinations in Africa and the developing world. As we speak, less than 10% of Africa’s population, which is 1.3 billion people, has been fully immunized. I believe we have a gap. We need to go further to reach the 70% target. WHO has established. If we are to stop the emergence and spread of new variants, then this year is the year we must vaccine at speed and scale. We saw the Omicron example. Omicron taught us the lesson that any threat anywhere on the planet is a threat anywhere on the planet. We must use all of our resources to increase vaccination, but in a more deliberate way that encourages stronger partnerships and collaboration.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Dr. Nkengasong: Why are these still some of the most pressing needs, especially in Africa?

DR. JOHN NKENGASONG: Access to vaccines was the first problem facing the continent. You may recall that the continent had very limited access last year to vaccines, including AstraZeneca doses purchased by the government. COVAX India had banned the use of this vaccine, so the continent was left with very few vaccines. We are now beginning to see a shift in this narrative, with more vaccines arriving on the continent. COVAX– from the African Vaccine Acquisition Task Team, and from bilateral donations such as those offered by US government, which the continent is very grateful for.

But we have to shift our focus now to vaccinating — that is, making sure vaccines that arrive at the airport actually get into the arm of the people. Eighty percent of the population in Africa — 80% average — are willing to accept vaccines. There’s a 20% minority that are hesitant, but we can work on that. But let’s build the right alliances, partnerships, to get the 80% of the population that is keen to be vaccinated vaccinated. This is the only way to save everyone around the world simultaneously.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Now, you also wrote an op-ed piece For The New York Times recently that was headlined “There Will Be Another Variant. Here’s What the World Can Do Now.” What are some of the steps that need to be taken now, because, as you say, inevitably, there will be more variants?

DR. JOHN NKENGASONG: The world must do a few important things. They should do them collectively and not in isolation. One is to increase vaccination. We’ve discussed that. The second is to test. We need to make sure that we have — we decentralize testing and make sure that the communities lead and own testing.

We need to improve our ability to monitor these variants so that we know exactly what they are and what their properties are and then take action. And, of course, ensure that this is linked to accessing new drugs. There are many new treatment options, including the Paxlovid and others. They should be easily accessible so that people can be tested for positive results and connected to treatment centers.

And lastly, let’s not let down our guards on the prevention measures. The prevention measures against — that we’ve used all through this pandemic — wearing of masks, avoiding large gatherings — work against all variants. Those should be maintained. Those are the main things we need to do in 2022. We must also do all of them together.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to ask you about Moderna’s chair and co-founder, Noubar Afeyan, who was asked about patents by CNN’s Fareed Zakaria in an interview last month.

FAREED ZAKARIA: Let me ask about this. Many people or certain people think you guys should give this technology away, and waive all your intellectual patents. Explain what Moderna’s position on this is. As I understand it you are willing to state that you won’t enforce patents for as long as COVID It is everywhere.

NOUBAR AFEYAN: Well, Fareed, the first time we spoke was around the time a year ago when we voluntarily pledged — the only company to have done that — voluntarily pledged not to enforce our patents against anybody who uses our patents to make a vaccine against the pandemic. At that time, there had been no proof that the vaccine will work, but we did that because we thought it’s the right thing to do from a vaccine access standpoint. We believe this has allowed others making mRNA vaccinations. And if others do that even further, that’s great.

AMY GOODMAN: So, that’s Moderna’s chair and co-founder. But, Dr. Nkengasong, there’s a difference between not suing a company for taking their recipe and revealing what that recipe, that formula is so that companies around the world could manufacture it and make it available, on the continent of Africa, in Asia, throughout the world. You have written and spoke about this at the World Economic Forum last week, when you said that during the pandemic we’ve seen a shameful collapse of global solidarity and cooperation. Can you talk about what these companies, that have made billions of dollars, paid for, in the research for them, in the case of Moderna, by U.S. taxpayers — Pfizer, because of its profits — paid for by the people, but not sharing these formulas? What impact has this had?

DR. JOHN NKENGASONG: So, this is a — we are living in an unprecedented time and dealing with a crisis that we’ve not witnessed for the last close to a hundred years. So that means the solidarity, that I’ve always been a champion of, has to be in play, solidarity that says that we need to bring all assets to the table to enable or increase availability or access of vaccines, including transfer of technology and also rights, and support for countries and regions to be able to manufacture vaccines, so that the issue of limited access to vaccines is overcome.

We are very encouraged to see countries like the United States already taking a position that favors this. We hope that other developed countries will follow their lead. I’m also very encouraged that about 10 countries in Africa have now embarked on the journey of producing vaccines in their respective countries. South Africa, Senegal and Morocco, as well as Egypt, have all accepted responsibility for producing vaccines in Africa. They should be supported and praised for this.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Doctor, I would like to ask you about the number of shots that would protect you. COVID. We’re now seeing in countries like Israel now recommending a second booster. We’re talking about four shots in a period of about a year. It’s not really logistically possible for the world to keep up this kind of a vaccination program. What do you think the vaccine manufacturers should do in the future?

DR. JOHN NKENGASONG: It goes back to our discussion a few moments ago about increased access to vaccines. I believe that the new generation vaccines will make it possible to have the third, fourth, and fifth doses less frequently.

The problem we face right now is how do we get people who are struggling to get that one shot to get it? How do we help those who have already had their first shot in Africa to get their second shot? I think the problem needs to be contextualized, so that we know exactly that you just cannot be aiming at the third and the fourth shot in Africa, where you don’t even have access to the first shot of the vaccine. This is what I believe is important. We need to focus on vaccinating at scale and vaccinating quickly, especially in areas with limited vaccinations.

AMY GOODMAN: Do you know anything about a variant that is coming out of Cameroon and has also affected France? Doctor?

DR. JOHN NKENGASONG: We have very little information about this variant and have not seen any published data. And we hope — truly remain hopeful — that that is truly not a variant of concern.

AMY GOODMAN: You can also talk about expired vaccines. What does it mean when there are millions of vaccines in Africa. And really, let’s look at those numbers. You have NPR reporting You have a lot of Africa’s midsection, including powerful political and economic players like Senegal, Nigeria, and Kenya. All this is under 2% vaccination rates. Away from Africa, you’ve got 10%. People haven’t gotten about 10% COVID Vaccine coverage in Syria, Afghanistan, and Haiti.

DR. JOHN NKENGASONG: Yeah. A vaccine that expires can be very painful as it could potentially save a life. But we should go beyond that and say, “What are the reasons that vaccines are expiring in Africa?” The first major reason is that those vaccines arrive with a very short lifespan, which is what you call the expiring date. We have provided guidance to all donors that vaccines intended for shipment to Africa should have a longer expiring period, at least three to six more months. This is so that countries can plan to use the vaccines when they arrive. About 0.5% of all vaccines have expired since they arrived on the continent. But again, I want to be very sure that I’m clear on this: Any expired vaccines that are on the continent is painful, because that is potentially a life that could be saved.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Could you also talk about the successes of some African countries in their efforts to stop the spread of HIV/AIDS? COVIDIt is not surprising, considering the amount of experience that some had in dealing with Ebola epidemics in their past.

DR. JOHN NKENGASONG: The continent has used a variety of previous experiences in fighting the COVID pandemic, and mobilizing the community. I’m referring to the Africa CDC, we’ve deployed over 18,000 community healthcare workers in several countries that do door-to-door engagement, human contacts, counseling and spreading of — helping the contact tracing early on in the pandemic.

The second thing that the continent has done well is their cooperation. They’ve set up mechanisms like the African Vaccine Acquisition Task Team, which is a great symbol of intercontinental cooperation and collaboration, which has enabled the continent to secure over 450 million doses of vaccines. This is remarkable. It is the first ever time in the history a disease has brought together a continent under the strong political leadership of President Cyril Ramaphosa, who was chair of African Union.

These experiences must be preserved and institutionalized so that we can use them to combat future pandemics and endemic diseases. Let’s not forget that malaria, tuberculosis and HIV There are still grave health threats in Africa.

AMY GOODMAN: Yes, let’s follow up on that. Dr. Nkengasong, you’re not only the director of the Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, but you are also nominated by President Biden for ambassador-at-large and coordinator of the U.S. government activities to combat AIDS/HIV globally. You can also talk about how the pandemic affected other diseases and populations, such as TB. HIV/AIDS, etc.?

DR. JOHN NKENGASONG: We are grateful. I’m truly grateful to President Biden for the nomination, but it still has to be confirmed. So, once that confirmation occurs, I’ll be at ease to speak more about the HIV pandemic.

Let me just say, very broadly speaking, that the disruption that COVID The impact it has had on the continent is enormous. I mean, there’s no doubt about that. The Global Fund has evidence that clearly shows that services that are geared towards tuberculosis or malaria can be rendered. HIV severe disruptions. That is what pandemics are for. If you stop people from moving, or if you disrupt supply chain management, it can have a severe impact on nongovernmental organizations.COVID-related affections.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And I wanted to ask you — during the pandemic, wealthier nations, like the United Kingdom, have relied on African doctors and nurses to shore up their health services. You’re calling on many of these doctors and nurses and health workers to return to Africa. Could you talk about this issue of the brain drain and of the — basically, the use of medical people trained in other countries by the wealthier nations?

DR. JOHN NKENGASONG: Absolutely. We learned a lot from this pandemic and created the African Task Force. COVID Response is an intercontinental taskforce which coordinates the response to the level of heads of states. And it was very interesting that so many Africans in the diaspora were willing to contribute — and contributed significantly — to the different technical working groups that were set up within this task force.

That suggested to us that the African Union and Africa could be merged. CDC A program would be established that will enable Africans living abroad to bring their experience and skills to the continent. This will yield a remarkable return. This will allow them to help the continent, with its very limited human resource for health, at least to address the issues that we face. So, we are very serious about this.

AMY GOODMAN: We are very grateful to Dr. Nkengasong. You’re usually in Africa, born in Cameroon, but you’re in Washington, D.C., right now. What do you find, coming to the United States, the difference in how the people of the United States are dealing with, their attitudes toward, how the government is dealing with Omicron — but, overall, coronavirus — and the African continent?

DR. JOHN NKENGASONG: We must admit that the Omicron variant of the virus is a lesson in how difficult this pandemic is. It’s a difficult virus we’re dealing with. It’s a virus that mutates very quickly. It’s a virus that if you allow it to circulate, it’s going to create mutations and challenge even the vaccination efforts that we’ve had in the world.

We should be encouraged by the leadership that the United States has shown in making vaccines more accessible to Africa. The United States has donated most vaccines to Africa. And the continent — I can speak on behalf of the African Union — is extremely grateful for that. Going forward, the United States will need to show more solidarity and leadership in resolving this global problem.

AMY GOODMAN: We would like to thank Dr. John Nkengasong for being with us. He is the founding director of Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This institution belongs to the African Union. President Biden recently appointed him ambassador-at-large and coordinator for U.S. government activities. AIDS/HIV globally. If confirmed, he would become the first African to hold this post. We will link to New York Times op-ed that Dr. Nkengasong wrote, headlined “There Will Be Another Variant. Here’s What the World Can Do Now.”

Coming up, we will look at both the January 6th House committee and federal prosecutors, what they’re finding when it comes to the Capitol insurrection, and how that relates to a fascinating new book, Gangsters of Capitalism: Smedley Butler, the Marines, and the Making and Breaking of America’s Empire. Stay with Us